Jack Shenker | The National

For over 24 hours earlier this month, a village in southern Gaza was devastated by an Israeli army attack. Jack Shenker revisits a day of destruction.

Khoza’a village has a small white-brick mosque, a smattering of donkey carts and a rusting water tower. It has neat rows of olive and citrus trees, and low-cut picket fences shading the main street. But the first thing that greets you as you enter the southern Gaza village from the west are its demolished houses: slabs of destroyed domestic comfort stacked and folded in on each other in impossible-looking ways.

They have shed their loads onto the alleys below, where they sit amongst rubble-shard mountains and steel reinforcement rods standing starkly in the wind.

Everyone in Khoza’a has a story about what happened when Israeli forces launched a 24-hour assault on their farming community of 12,000 earlier this month. It began when Apache helicopters appeared overhead late in the evening of January 12th, day 17 of Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s three week onslaught of the Gaza Strip. Mohammed al-Najar’s wife was giving birth that night in a hospital in nearby Khan Younnis; the missiles stopped him from witnessing the arrival of his new son. Instead, he spent the early hours of the 13th quieting the cries of the village’s infant population.” They were screaming that night,” he told me. “They screamed through the bombs and they screamed through the jokes and soothing prayers we whispered to calm them down.

Khoza’a isn’t screaming anymore, but it is garrulous, every corner stumbling over itself in an effort to tell its story. Kids swarm around in excited packs; I can’t move without wrinkled black munitions balls being pressed into my hand, or serial numbers from rockets being thrust before my camera.

The first independent investigators entered Khoza’a on January 14th. Over the next eight days, local researchers and I conducted interviews with as many of its residents as possible, including local paramedics and doctors who dealt with the wounded. Many of their witness statements are corroborated by testimony collected by the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem and Palestinian researchers.

The attack on Khoza’a began at 9:30pm on January 12. For over five hours, the village was blanketed by F16s, helicopter gunships and unmanned drones. At 3am on January 13, the second phase of the attack began when Israeli bulldozers trundled up to a cluster of houses on Khozaa’s eastern fringe, a mere 500m from the “green line” separating Gaza from Israel. Scared and confused, the residents of these buildings poured onto their roofs, waving white flags under the cold night sky. “There were over 200 people from 36 families up there calling down to the Israelis,” remembers 29-year-old Iman al Najar.

As their houses were demolished one by one, a stream of people headed 100 metres uphill to the west to a small, grass-strewn courtyard off a paved alleyway, dodging fire on the way. There they were flanked by walls on three sides and sheltered from the surrounding buildings, where IDF special forces had taken up positions. As night ticked away and the small 7m x 10m square filled up with villagers, it became clear that the Israeli soldiers were intent on levelling every house on the eastern street. Rawhiya al Najar, a 50-year-old mother of three, ran back to her street to urge those still in their homes to evacuate. By 7am, when she had reached the last house, all 200 of the former roof-wavers – over half of them children – were now gathered in the courtyard. Trapped between bullets and bulldozers, the villagers had nothing to do but wait.

One kilometre to the west, on the opposite side of town, members of Rawhiya’s extended family had formed an assembly of their own. Over 20 al Najars were taking refuge in the house of Khalil, their elderly patriarch, having been forced from Riyad al Najar’s home across the street by rocket fire. As explosives pounded the area from land and air, the children were now wedged quietly under the stairs. “The adults thought this would be the safest place to be if the building collapsed,” recalls Joma’aa, 18. They were wrong. A rocket sliced through the roof and the first floor and landed under the stairs, where 16-year-old Ala’a and her 15-year-old brother Ayman had taken cover. Most of Ala’a’s waist and pelvis was blown away, as was a third of her face; she eventually died after 10 hours of surgery in Khan Younis hospital.

Ayman survived, but the burns he received were so severe that his bones were visible through the wounds. Five more missiles quickly followed, taking the lives of a 22-year-old neighbour and 75-year-old Khalil himself, who had chosen to sit out in the garden to watch his village light up with gunfire. A rocket split him in half, and his family had to lay him to rest twice; they only discovered his legs a day after burying his torso.

Stunned by the volley of explosives, the rest of the family escaped across the alley to another home, where they huddled together on the ground floor. The drones spun around and followed accordingly. First a series of missiles blew holes in all the buildings, then white phosphorus flares looped down and into the holes. This time a young boy was hit in the eyes and legs; his skin, coated in chemical toxins, could not be touched. “Trying to pick him up was like trying to carry sand or liquid in your hands – he was just falling apart,” said one relative.

Since the dead and dying were covered in phosphorus, they had to be left behind as the group sought safety once again, clambering over a low back fence and back into Riyad’s house. Having run out of homes to protect them, the al Najars – filthy, exhausted, and fewer in number than ever before – were back where they started.

It was now 8am. Back in the grass-strewn courtyard, Rawhiya and her tightly-packed companions were in a similarly tight situation. Having finished with the houses, Khoza’a’s concrete-razing visitors were moving on – to the very space where the newly homeless were now trapped. Eight bulldozers surrounded the courtyard’s northern wall and began crunching into it, sending rubble flying forward. Each time the crumbling outer wall showered the villagers with metal and concrete, the courtyard became smaller and more claustrophobic.

Realising that they would all soon be crushed, Rawhiya grabbed a white flag, got a small group together, and tentatively stepped out in the alleyway to see if it was safe. Several villagers claim that Israeli soldiers shouted across at them to turn right and head up the path; they complied. “Rawhiya and I were at the front, followed by the rest of the women, then children, then men,” recalls 23-year-old Yasmin al Najar, her neighbour. “As we rounded the corner, I saw a special forces soldier in a window at the end of the street. He smiled at me and we thought that meant ‘go ahead’, because they were telling us our evacuation had been co-ordinated. So we went ahead and they shot Rawhiya in the head.”

The bullet was fired by a sniper in a house the Israelis had commandeered at the start of the incursion. They had two hostages in the basement: a 14-year-old boy and a woman in her 40s. The boy was Iman al Najar’s brother, Mohammed.

Outside, there was chaos. Fragments of Rawhiya’s bullet had sprayed Yasmin too; clutching at her wounds, the young woman spun around and followed the others back into the courtyard. When their supposed saviours returned blood-spattered and shrieking, the villagers who had waited behind moved closer to outright panic. Mobile phone calls were put in to emergency services in the hope that the Palestinian Red Crescent would be allowed to come in and save Rawhiya. The answer came through shortly afterwards: the Red Crescent had contacted the IDF and been told that Khoza’a was now a closed military zone. Medical staff were not allowed to enter. Witnesses claim that one ambulance that attempted to reach Rawhiya anyway was shot at from the ground and air, forcing the paramedic, Marwan Abu Raeda, to seek cover in a nearby house. He was not able to remove Rawhiya’s corpse until 8pm: she had taken almost 12 hours to die.

Meanwhile, the villagers had a desperate choice to make. “We had to decide – death by rubble or by guns,” explained Iman. “I didn’t want to be buried alive, nor did anyone else. So I said to everyone, we have to stay together; we either live together or die together.” The villagers agreed and sunk to the floor, slowly crawling as one out onto into the alleyway.

At noon, bits of shrapnel were still flying through the air from rocket attacks on nearby houses. Iman led the villagers (including Yasmin, who had tied some loose fabric to her leg to stem the bleeding) out on their hands and knees across the pathway where Rawhiya lay, alive but dying under the midday sun. The group made it to a UN school 300 metres away just before helicopters swooped back in for a new round of devastation. Inside, they called the Red Crescent again. But with Israeli special forces still manning positions along the street, only one ambulance could make it to the gates. “We insisted on the children getting out first, but there were so many of them and just one ambulance. They were climbing all over each other in terror to try and get inside,” recalled Iman. Those children who couldn’t fit in the ambulance stood banging their heads against the school walls.

Marooned in their separate corners of the village, Khoza’a’s residents waited for the missile fire to ebb away. By the evening it had stopped, and the hunted started edging out of their hiding-holes. Evacuations got underway. One particularly courageous organiser was Mahmoud al Najar, a 55-year-old father of three, who shepherded residents from the bullet-torn backstreets into cars and trucks driven over by concerned relatives. Mahmoud had been unaware of the dramas faced by his family members across the village; several members of the al Najar family report that when he heard that Rawhiya had been shot, he strode back towards the courtyard pathway to look for her. As he was heading to search for his relative in the gloom, a single shot from a special forces sniper hit Mahmoud in the head. He died instantly.

(The IDF, contacted for comment said, issued this statement: “The IDF does not target civilians. For 22 days the IDF fought an enemy in Gaza who does not hesitate to hide behind civilians and fire from humanitarian aid facilities. IDF forces have clear firing orders, but in the complex situation in which fighting takes place inside towns and cities, placing our forces at great risk, civilian casualties are regrettably possible. In response to the claims of NGOs and claims in the foreign press relating to the use of phosphorus weapons, and in order to remove any ambiguity, an investigative team has been established in the Southern Command to look into this issue. It must be noted that international law does not prohibit the use of weaponry containing phosphorus to create smoke screens and for marking purposes. The IDF only uses weapons permitted by law. The IDF is obligated to international law, and in light of the [claims made in this article] some of the issues will be investigated.”)

By the time night fell on January 13th, 14 residents of Khoza’a had been killed, 50 lay wounded, and 213 had been taken to hospital for gas inhalation. Given the scale of destruction wrought by the invading army Khoza’a’s death toll was remarkably low. Indeed, the village’s story is significant largely because it is so ordinary.

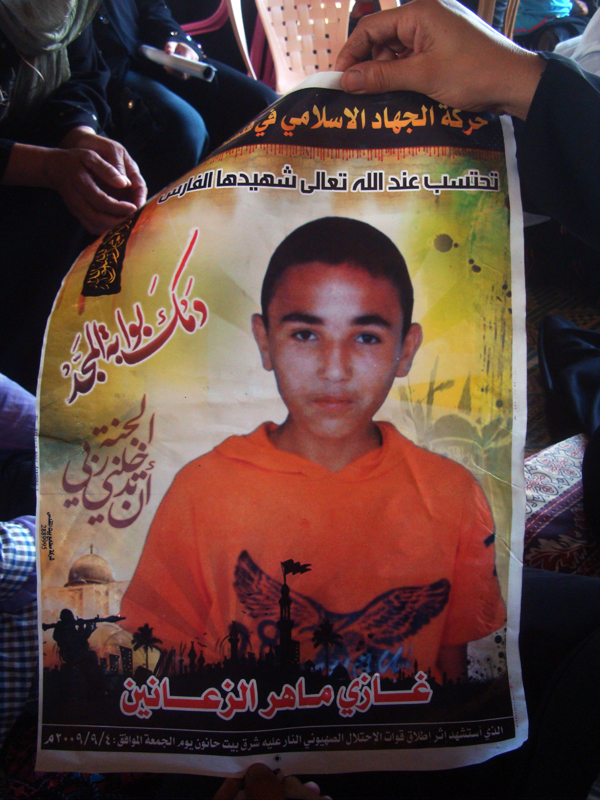

Geography has etched violence into Khoza’a’s landscape for years. Farmers tending their fields regularly come under fire from Israeli troops across the border. Only two days prior to the invasion, a string of air strikes had devastated a group of houses near the “green line”. Seven months earlier – just two days before the old ceasefire came into effect – Aiya al Najar, an eight-year-old girl, was shot by an apache rocket as she stood on the roof of her home. It tore her body apart so extensively that they carried it away in buckets, “like pieces of meat in a plastic bag”, according to one cousin. Two years before that Aiya’s brother, 18-year-old Zaki, was shot dead in a ground operation.

Residents are adamant that the closely-knit village has never been a base for Hamas fighters. They are convinced that the attacks are part of the Israeli state’s plans to expand its border buffer zone westward. “They wanted to send a message to our village: ‘Leave, leave your land behind,’” says Samer al Najar, Yasmin’s father, while monitoring his daughter’s recovery at home. “But this was the land of our fathers and will be the land of our children, so we stay. We sleep in tents in the rubble rather than finding shelter elsewhere. And although there is no armed resistance here, amid this violence the act of staying becomes a resistance, and that is why they are afraid of us.”

Nor has the incursion really ended, at least in the minds of those who bore it. The day before I visited Khoza’a, a local who was inspecting the municipal water lines near the border – in co-ordination with the Israeli authorities – was shot at by troops, three days into a supposed ceasefire. The day after the cessation of hostilities was announced, Maher Abu Rajila ventured down to his farmlands to inspect the damage caused by the bombardment. He was killed by gunfire from within Israel. The children who sought shelter in the UN school are unwilling to return. “They’re too scared,” Imam tells me flatly.

In the aftermath of Khoza’a’s incursion, it’s the inanimate objects that stand out. Ala’a’s school notebooks flutter in the wind, blown open to the elements by the bombs that also twisted her bedroom upside down. Dusty teacups stand neatly to attention on kitchen windowsills bereft of their kitchens, the rest of the home curled up in pieces in a nearby street. These are the details that residents of the village keep pointing out to me, along with the animals and foliage: sheep, pigeons and trees mowed down from the sky.

Trails of phosphorus from the incursion remain buried under sandy ditches on the side of the road. Expose them to air and they burst into flames again; douse them with water and they splutter back into life within seconds. The kids kick them around sometimes for fun, half-heartedly pulling their jumpers up over their noses to smother the fumes. Last week, a nine-year-old boy named Adam al Najar took hits to his legs and chest when he triggered an unexploded landmine.

“They keep us awake at night with their bombs so we can’t sleep like other people sleep,” says Iman. “They fire missiles at our streets so our children can’t play like other people’s children. They bulldoze our land so our trees can’t grow like other people’s trees. But no matter how many they cut down, we will plant more and keep on standing.”